UW-Parkside Professor Aids in Identifying New Prehistoric Crocodile Species

UW-Parkside’s Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Chris Noto, working with a team of other archaeologists and professors, assisted in the discovery of a new prehistoric crocodile species.

Around 95 million years ago, a giant relative of modern crocodiles ruled the coastlines and waterways of what would one day become north-central Texas. Adults of the newly discovered and described species Deltasuchus motherali grew up to 20 feet (6 meters) long in life, and left behind bite marks on the fossilized bones of prey animals letting us know that it ate pretty much whatever it wanted in its environment, from turtles to dinosaurs.

Around 95 million years ago, a giant relative of modern crocodiles ruled the coastlines and waterways of what would one day become north-central Texas. Adults of the newly discovered and described species Deltasuchus motherali grew up to 20 feet (6 meters) long in life, and left behind bite marks on the fossilized bones of prey animals letting us know that it ate pretty much whatever it wanted in its environment, from turtles to dinosaurs.

Dr. Thomas Adams, Witte Museum Curator of Paleontology and Geology, in San Antonio, Texas, and lead author of the paper described Deltasuchus as one of the “top predators in its ecosystem.”

“The Arlington Archosaur Site is a very important and unique fossil locality. It preserves a nearly complete ecosystem from a time in Earth’s history for which we have very little of a fossil record,” said Dr. Chris Noto, associate professor of biology at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside. “During the middle of the Cretaceous period terrestrial ecosystems in North America were undergoing a major change, which would result in new groups of dinosaurs and other organisms becoming dominant—animals like Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex. But the story of how we got there, the timing of these changes and the players involved, is a story still waiting to be told. There is a growing record of this transition in the west, but we know virtually nothing about what was happening in eastern North America.

“Discoveries from the AAS are helping to fill that gap and provide a much more comprehensive picture of what terrestrial ecosystems were like during this time. Despite nearly a decade of continuous excavation, we are just now able to study the fossils and put them into a scientific context. We can expect more new species to be described and other exciting discoveries to come.”

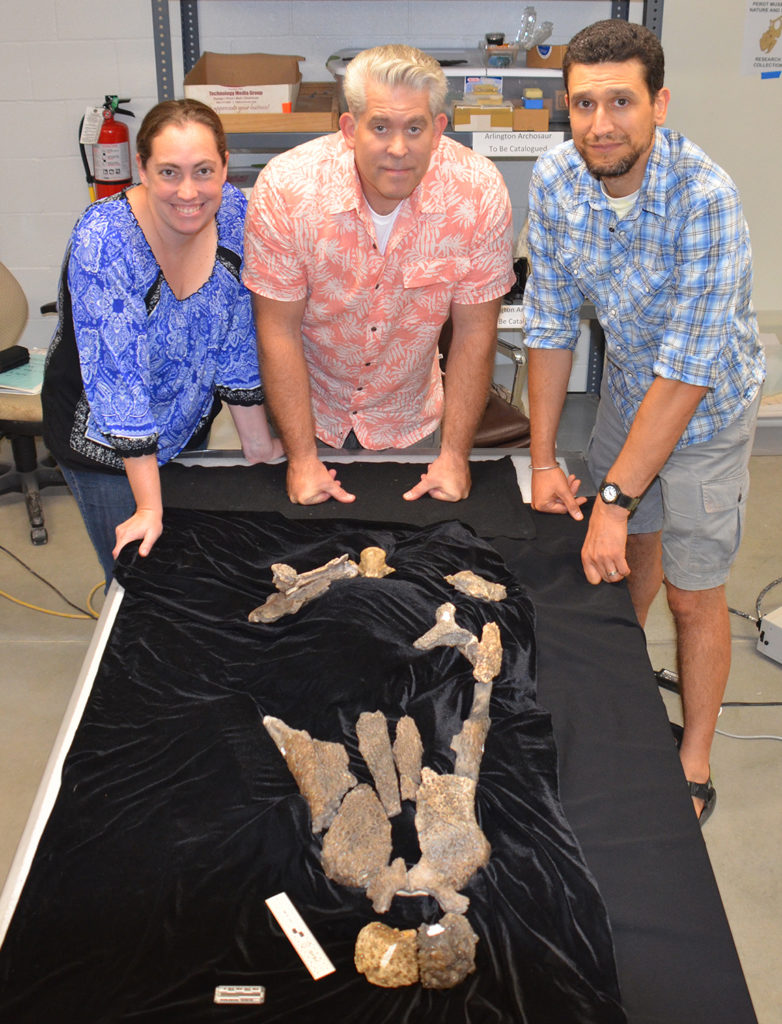

Dr. Adams, along with co-authors Dr. Noto and Dr. Stephanie Drumheller-Horton, at the University of Tennessee, published the description of the new croc species in the latest issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. An odd aspect of the find is that it was discovered in a place one normally doesn’t think to look for ancient fossils - in the heart of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex.

The site that produced the new species was discovered in Arlington, Texas in 2003 by amateur fossil hunters Art Sahlstein, Bill Walker and Phil Kirchoff. Dubbed the Arlington Archosaur Site (AAS), the area is undergoing rapid residential development, and paleontologists have been working with local volunteers and fossil enthusiasts to excavate the site over the last decade. Deltasuchus motherali is actually named for one of those volunteers, Austin Motheral, who first uncovered the fossils of this particular croc with a small tractor when he was just 15 years old. Work on the site is supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society, which is funding continued excavations and study of this unique fossil locality. Fossils from the site, including the Deltasuchus motherali bones, are part of the collections of the nearby Perot Museum of Nature and Science, in Dallas, Texas.

Deltasuchus is the first of what may prove to be several new species described from this prolific fossil site. The locality preserves a surprisingly complete ancient ecosystem ranging from 95 million to 100 million years old, and its fossils are filling in an important gap in our understanding of ancient North American land and freshwater ecosystems. While most of Texas was covered by a shallow sea at this time, the Dallas-Fort Worth area was part of a large peninsula that jutted out into this sea from the northeast. This peninsula was a lush environment of river deltas and swamps that teemed with wildlife, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, mammals, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, and plants.

Noto spoke about the contributions of UW-Parkside students to his research. “Parkside students have been involved in a number of ways,” he said. “I have had students come to Texas to do field work with me. Currently several students in my lab are searching through sediment samples for tiny fossils we would otherwise miss, and has the potential to add even more new discoveries. I have a partnership with the Carthage Institute of Paleontology (located in the Dinosaur Discovery Museum in Kenosha) to provide internships for students to learn fossil preparation and lab techniques. Many of these students have conducted independent research resulting in numerous posters and presentations at conferences over the years.”