NEW SPECIES OF FOSSIL CROCODILE NAMED FOR LONG-TIME VOLUNTEER IS A ‘LITTLE NIPPER’ OF A BIG DISCOVERY

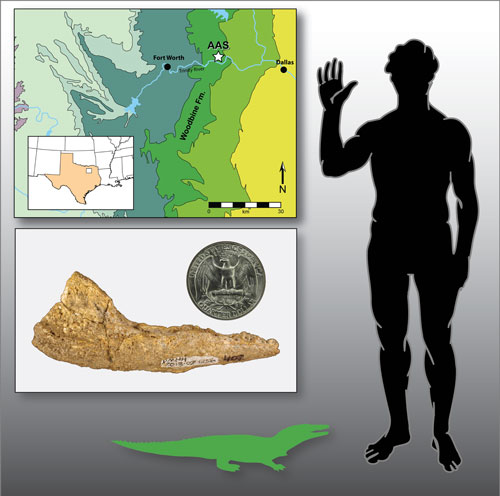

In the heart of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, paleontologists have partnered with a dedicated team of local volunteers and fossil enthusiasts to excavate a treasure trove of fossils dating from 96 million years ago, during the last period of the Age of Dinosaurs. Now, a new species discovered at the site is being named in honor of one of these citizen scientists, Arthur Sahlstein.

“The AAS wouldn’t be the success that it is if it weren’t for the small army of dedicated volunteers donating their time, energy, expertise, and resources,” says Dr. Chris Noto, lead author and Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Parkside. “It is only fitting that we honor one of our most valuable and prolific members.”

Mr. Sahlstein co-discovered the Arlington Archosaur Site in 2003 and brought it to the attention of paleontologists. He has remained a fixture at the site ever since, discovering numerous fossils including an unusual jaw from a small crocodyliform (a distant crocodile relative), now named Scolomastax sahlsteini.

Mr Sahlstein says, “The discovery of the Arlington Archosaur Site 16 years ago was a watershed moment that launched an amazing period of personal and academic discovery. I am very humbled to have this ‘Little Nipper’ carry my name. This partnership will be a model for future major excavations.”

This isn’t the first time the team has named a new species for one of the Arlington Archosaur Site volunteers. In 2017, another new crocodyliform, this one a 20 foot long top predator, was named Deltasuchus motherali after Austin Motheral, who was just 15 years old when he uncovered the fossils that would eventually bear his name.

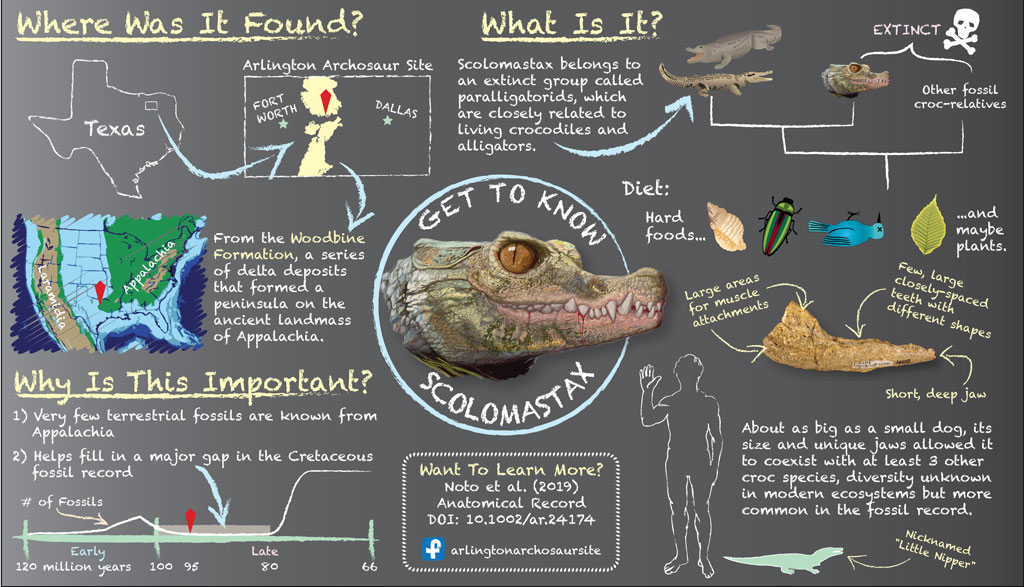

The name Scolomastax means “pointed jaw” in Greek, referring to its tapered, V-shaped mandible. The 1 to 2 meter long new species is named in the current issue of the journal Anatomical Record.

“People sometimes think that crocs haven’t changed much since the Age of Dinosaurs, but that just isn’t true,” says paper co-author Stephanie Drumheller-Horton, from the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of Tennessee. “This little croc has several weird features that make us think it ate hard prey items and maybe even plants. We don’t have anything like it alive in the world today.”

But Scolomastax is important in other ways, too. “This new species belongs to an extinct group of crocs called paralligatorids”, explains Dr. Alan Turner, an Associate Professor at Stony Brook University and a co-author on the study. “They have an extensive fossil record during the Cretaceous period in Asia but remain less well-known in North American deposits. Scolomastax is important in part for expanding our knowledge of this intriguing group.”

The landscape where Scolomastax lived also differed greatly from modern day. In the mid-Cretaceous, the heart of North America was covered in a shallow inland sea, cutting the continent in two. The Arlington Archosaur Site represents a rare assemblage from the eastern landmass, known as Appalachia. It would have appeared not unlike the Mississippi River delta 96 million years ago, with warm, swampy conditions and a variety of organisms living across land and water. Scolomastax and several other species of crocodyliform would have lived side by side with a diverse assemblage of dinosaurs, turtles, amphibians, mammals, fish, invertebrates, and plants, several of which are also new species awaiting description.

Work at the Arlington Archosaur Site is supported in part by the National Geographic Society, who provided a grant to complete field work at the site, and the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas, who curates all the fossils found at the site and organizes the many volunteers who work there. Currently excavations at the AAS are on hiatus as the research team works on describing the thousands of specimens that have already been discovered. Notes Mr Sahlstein, “The site has not ceased to give up its secrets.”

This project was also featured in National Geographic. You can read that article by clicking the link below. Also, UW-Parkside Executive Director of Marketing & Communications John Mielke interviewed Dr. Noto for Parkside Today, which you can listen to by clicking the link below. The interview will air on WIPZ 101.5 FM on Tuesday, June 24, at 4 p.m.

Parkside Today: Dr. Chris Noto

AUTHOR CONTACTS:

Christopher Noto Ph.D.

University of Wisconsin–Parkside

Department of Biological Sciences

262-595-2213

noto@uwp.edu

Thomas Adams Ph.D.

Witte Museum

Curator of Paleontology and Geology

210-357-1852

thomasadams@wittemuseum.org

Stephanie Drumheller-Horton Ph.D.

University of Tennessee-Knoxville

Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

865-974-2366

sdrumhel@utk.edu

Alan Turner

Stony Brook University

Department of Anatomical Sciences

631-444-8203

alan.turner@stonybrook.edu

PEROT MUSEUM CONTACTS:

Ron Tykoski Ph.D

Perot Museum of Nature and Science

Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology

Perot Museum of Nature and Science

214-756-5726

ron.tykoski@perotmuseum.org

Anthony Fiorillo Ph.D.

Perot Museum of Nature and Science

Vice President of Research and Collections and Chief Curator

214-756-5752

tony.fiorillo@perotmuseum.org